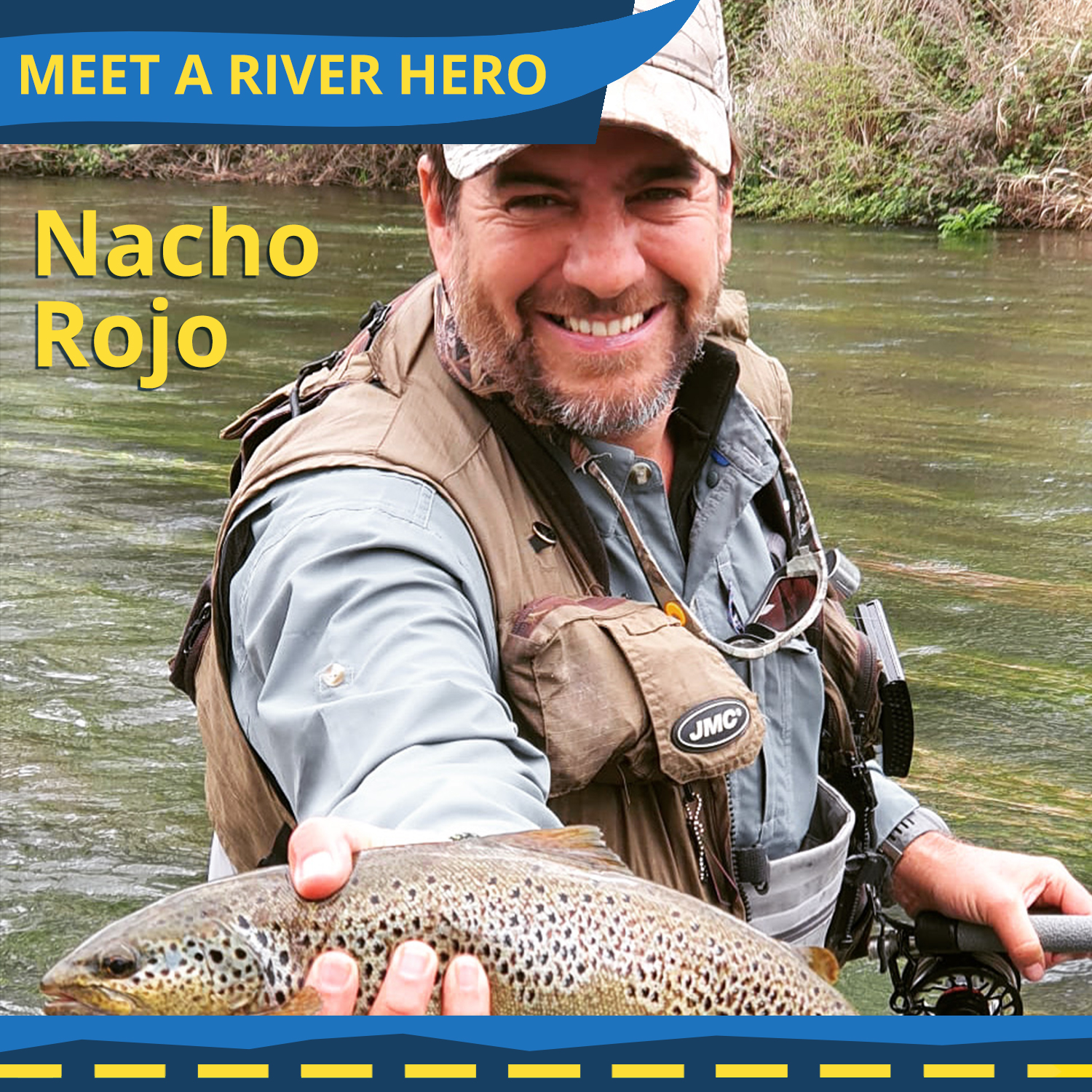

Nacho Rojo wears many hats – he is a biologist, an avid angler, president of the Association of Anglers for the Conservation of Rivers (APCR), and content creator for Caza y Pesca TV. His passion for fish and free-flowing rivers makes him a true River Hero.

Back in the day, the Bornova River was a trout paradise, but man-made barriers took a toll on the trout population. That’s when Nacho stepped in. Following the green light from the Tagus River Basin Authority, Nacho and his team removed an obsolete weir armed with only a trusty donkey, a jackhammer, and heaps of dedication.

Read the inspiring interview with Nacho Rojo, the Spanish River Hero, and learn more about the weir removal on the Bornova River.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Welcome Nacho! Can you tell us a bit about what you do?

[Nacho] Well, I am a biologist, angler, and president of the APCR. Right now, I work as a content editor for Caza y Pesca TV, an outdoor TV channel on Movistar Plus in Spain.

I am very much in contact with rivers, not only as an angler but also because I interview truly diverse people: people who are anglers, people who work in rural tourism, people who have a small factory, a cattle farm, everything! And so, I can feel a little bit of those vibrations that people have in the rural world and in the countryside.

You see, from the city, we are always very disconnected from what is happening, but there you can really see how the river barriers affect all sectors, not only biology but ecology in general. Also, from the point of view of the relations between people in society, and in the economic sense as well.

How did you find out that a barrier can be demolished?

[Nacho] We know that the barriers are there, and we know that they can collapse over time. We are aware that with a little effort, dam removals can be achieved. Here in Spain, it is complicated because there are many actors involved. For our removal, our relationship with the Tagus River Basin Authority in the Bornova River helped us. We managed to show the Authority that it was a small dam, and it was feasible, serving as a milestone, for bigger things.

Figure 2: The Tagus River Basin Authority made a notch on the weir, but fish could not pass through.

How did you choose where you wanted to demolish your first barrier?

[Nacho] The Bornova River is a small river in the Tagus Basin, in which a large population of trout was present, but its population has been reduced. We decided, as a conservationist association, to focus on a space in which we could control the entire dimension of the river. We carried out a complex and complete study of environmental indicators, in which many different actors participated – professionals but also others who were not.

The goal was to find out what was happening to the river and draw conclusions. For example, we realized that there were many dams that were built to serve the most important silver mine in Spain situated in Hiendelaencina Municipality, along the Bornova River.

Figure 3: The administration permitted Nacho and his team to demolish the weir themselves.

What were the main challenges for this dam removal? What did you find most difficult?

[Nacho] Well, there were several challenges. The first major step was to convince the administration that this removal was necessary. We had the advantage of working with a colleague, Lidia Arenillas, from the Tagus River Basin Authority, who was already very qualified and aware of this issue. Once we managed to convince her, we had to speak with the locals, the mayor, and the National Heritage who confirmed that it was an abandoned infrastructure from the late 1800s. Afterwards, people suddenly started to care again and came out from anywhere with something to say. This made it difficult to try joining forces. We then told the Tagus River Basin Authority that, instead of demolishing all the infrastructure, they could make a notch in the weir. The Authority made a notch that did not go all the way down, impeding animals’ passage. Therefore, we asked the administration if we could demolish fully the weir ourselves. They told us that if we did it with our means, they would permit us to do it. And well, that is how we decided to proceed.

Looking back, it was a major source of pride, but also a bit crazy. The world is full of crazy people, and, in this case, the crazy ones are the first to lead the way. The truth is that it is extremely rewarding!

Video 1: Nacho and his team tearing down the weir with their own means.

What makes you most proud of in this entire process?

[Nacho] First, I am proud of the teamwork. This was a battle that opened a path to knock down more barriers. It is nice to see that there are interested people – they do not have to be engineers or biologists or anything. We just need normal people, like you, like me, like anyone, who can say “Hey, this is a goal that is worthwhile and must be done!”. That, for me, is the best.

The second thing I am most proud of is that we decided to proceed with removing the dam after doing an important and deep study. It was not a random decision. The decision was taken after an exhaustive and scientific study and with a clear justification. Convincing people with this previous work is very gratifying.

Video 2: Nacho and his team tearing down the weir with their own means.

What would you say to a government or administrative officer that would help the public support and execute dam removals?

[Nacho] In Spain, with the current legal system, each step takes an exceptionally long time, you must be strong mentally to be able to bear it. I would tell the administration that, apart from shortening the steps of the dam removal process, they should take advantage of the people who want to do things, and who enjoy it. They will not do it for free, but they will do it with all the enthusiasm in the world and with the desire that their children and others realize that it is possible to be proactive and recover nature. This is an example that we need in these times. Everyone is looking at themselves and almost no one looks in the rear-view mirror – they do not want to know what is happening behind them. It is a way to make people aware that in their interest, they can restore rivers.

If someone from the public wants to get involved, what would your advice be?

[Nacho] We are an angling association that likes fish a lot. We like to fish, but we also like (free) rivers. Many times, we go fishing and do not catch anything, but we like to see how a river runs freely. In other words, you do not have to be an angler, you can simply be someone who wants to change things for the better.

I would advise them that if there were something that bothers them or something that they believe could be improved, they should look for support and find people who also think like them. If we get together, we are stronger – more than we think. Together we have a lot of power, and we can open many doors.

So, get together, value your beliefs, and believe in yourselves.