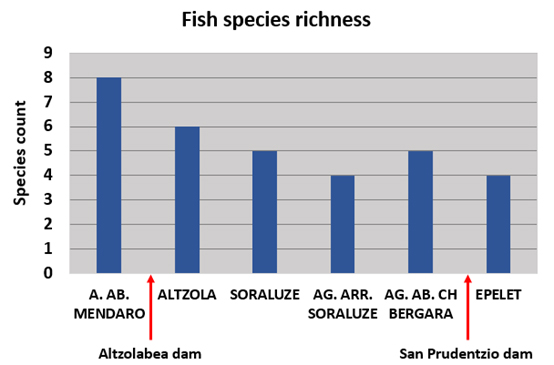

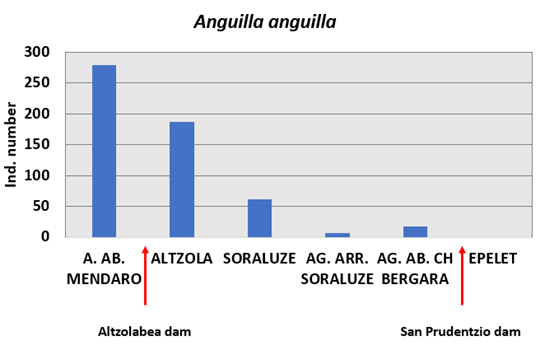

Alzolabea and San Prudentzio dam removals – Part of the River Deba basin restoration project

The River Deba

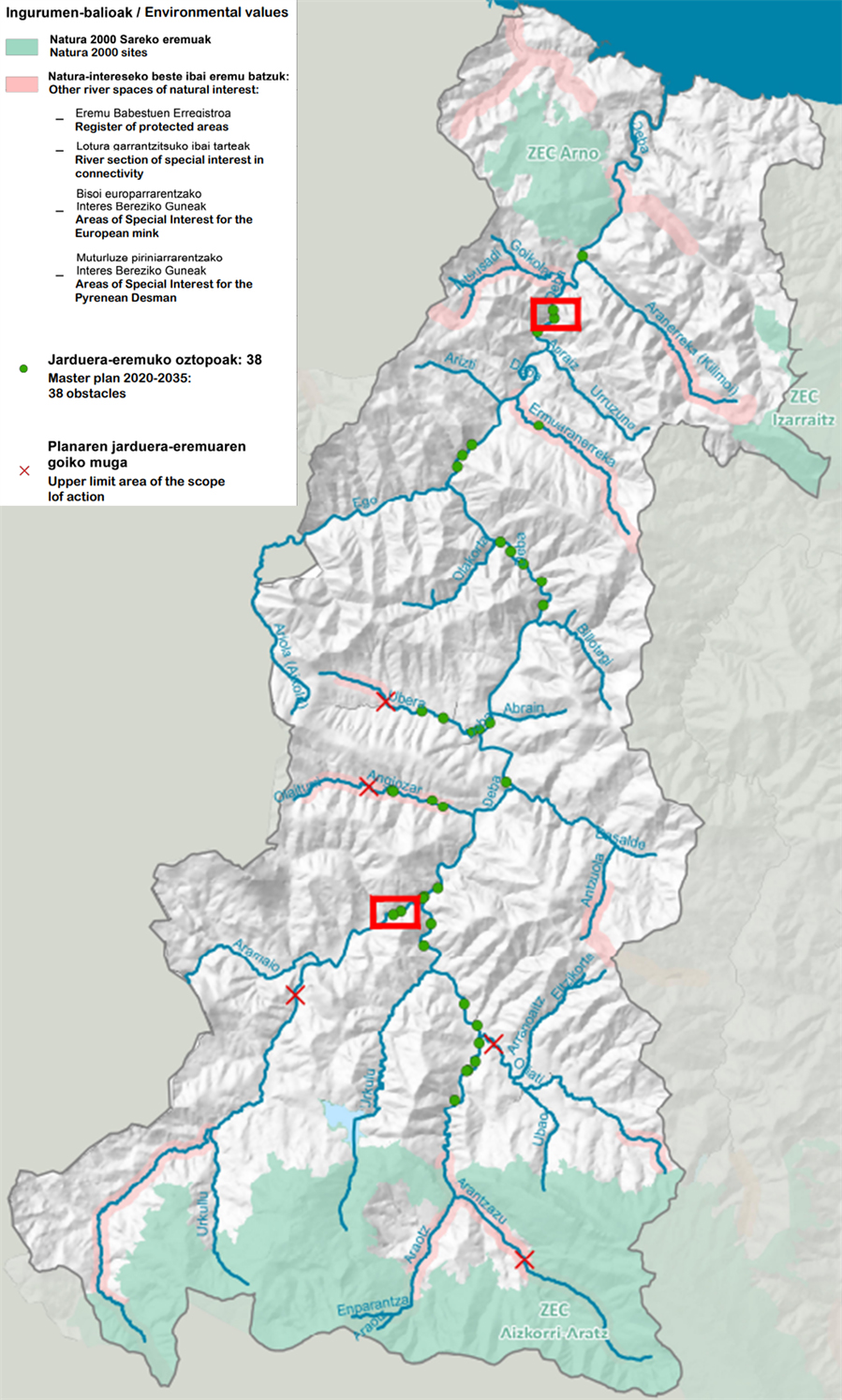

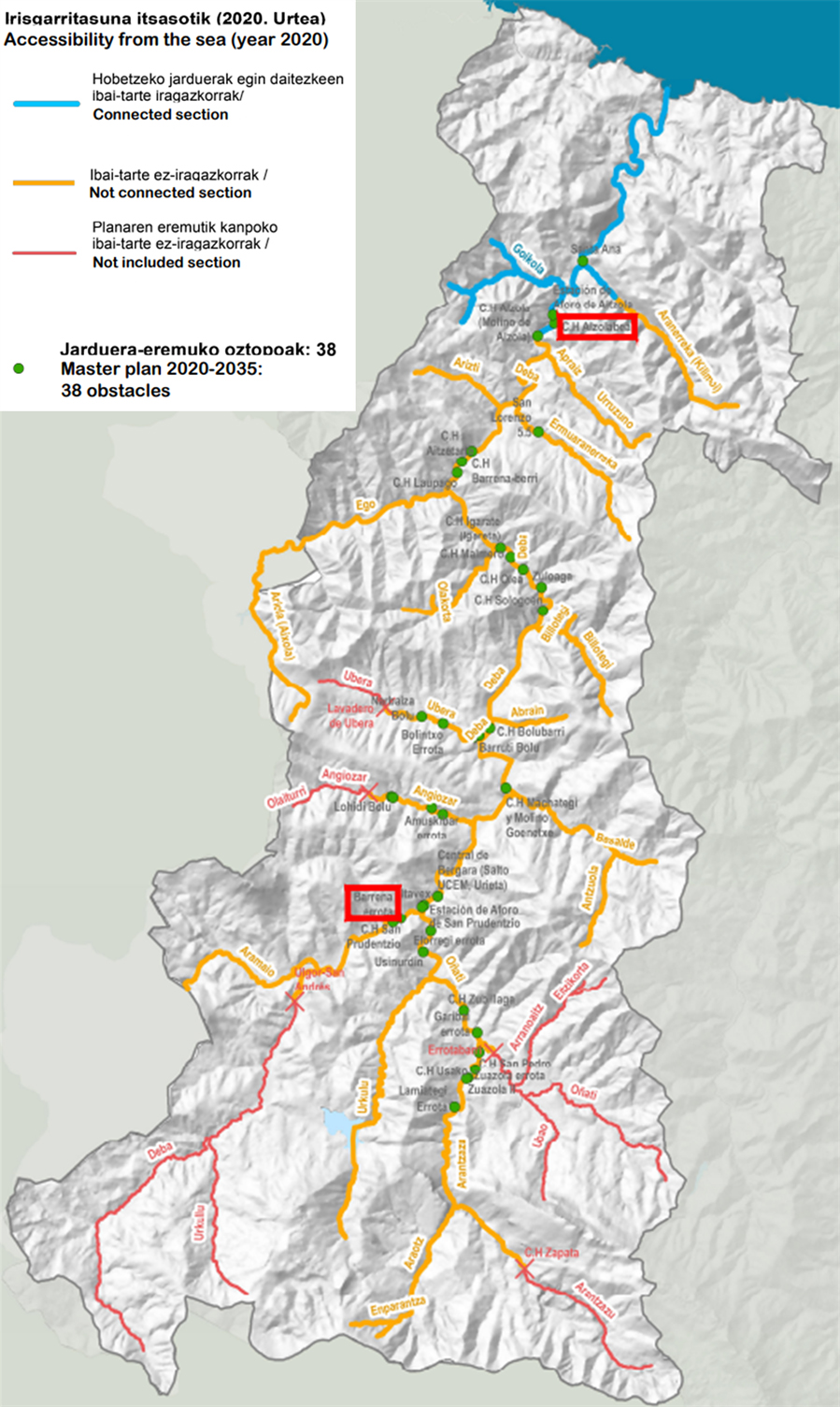

River Deba (Basque: Deba ibaia; Spanish: río Deva) is located in the Basque Country in Spain. It rises in Arlaban and flows into the Atlantic Ocean, in the Bay of Biscay, in Gipuzkoa Province (Figure 1). Its basin covers an area of 534 km2 and includes urban, peri-urban and agricultural areas, while ~135000 people live within it. The lowest section of River Deba borders with the ZEC Arno Natura 2000 site, while many of Deba’s tributaries spring from the ZEC Izarraitz and ZEC Aizkorri Aratz Natura 2000 sites (Figure 1). In addition, many of Deba’s tributaries are characterized as sites of natural interest; they are registered protected areas, sections of special interest in connectivity, areas of special interest for the European mink (Mustela lutreola) or areas of special interest for the Pyrenean desman (Galemys pyrenaicus), a small semiaquatic mammal related to moles and shrews. The former is characterized by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature’s) Red List of Threatened Species as critically endangered, while the latter as threatened.